Introduction

The major function of the stomach is to temporarily store food and release it slowly into the duodenum. It processes the food to a semi-solid chyme, which enables better contact with the mucous membrane of the intestine, thereby facilitating absorption of nutrients. In addition, the stomach is an important site of enzyme production.

Anatomy

Dogs, pigs and monkeys have several gastric features in common with humans. All possess a simple stomach; that is, there is only one major compartment. Furthermore, the stomach is lined with a glandular mucosa that secretes substantial quantities of gastric acid. The fundus and pyloric regions which contain the parietal cells responsible for secretion of gastric acid are much more extended in humans than in the pig, while being fairly similar between human and dog. Although officially an omnivorous species, pigs are predominantly herbivorous and, as a result, the gastric chamber is somewhat modified. For example, there is a diverticulum at the top of the stomach which is probably a site for microbial metabolism of ingesta and the percentage of parietal cell-containing mucosa is smaller than in humans (Dressman and Yamada, 1991). Furthermore, the stomach of pigs is much larger compared to humans, in the order of several litres.

Another relevant aspect in pigs lies in their susceptibility to gastric ulcers, with an incidence reported between 5 and 50% of the general pig population (Pond and Houpt, 1978), with usual incidence of about 20% (Tumbleson, 1986). In the primate family, the anatomy of the stomach varies between the different types of monkeys due to a huge variation in dietary habits (Jones, 1972). This naturally leads to a range of structural arrangements and relative dimensions within the gastrointestinal tract. However, for the commonly used primates, like the rhesus monkey, the stomach is simple (Dressman and Yamada, 1991). The stomachs of rodents are divided into a glandular and a non-glandular portion. The non-glandular stomach is used in the storage and digestion of food. The glandular stomach contains the gastric glands. The glandular stomach is a relatively small part of the total stomach compared with the glandular stomach of man (Kararli, 1995). The stomach of the rabbit is simple and lacks specialised regions.

Gastric emptying

Dogs and pigs, like humans, tend to ingest periodic meals which are followed by gastric emptying (Weis and LaVelle, 1991). In contrast, rodents and rabbits are continuous feeders and therefore the stomach is never empty.

There are some important differences in gastrointestinal transit between pigs and humans. In pigs, the emptying of food from the stomach is bimodal, with about 30 40% of contents emptying in the first 15 min, followed by a more sustained emptying about 1 h later (Pond and Houpt, 1978). Emptying also appears to be incomplete in pig, so there may be food present in the stomach 24 h a day. The ability to retain food in the stomach for such a long period may lead to the false assumption that one is studying the pig in the fasted state, when, in fact, there is still food present.

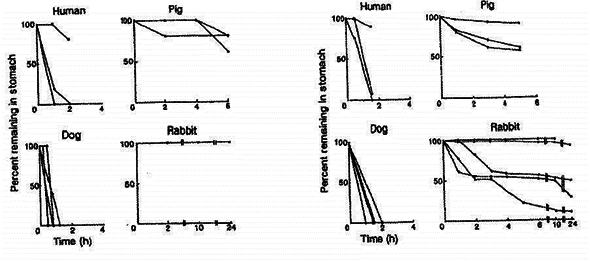

Differences in gastric emptying between the species can be seen in the figure below.

Left: fractions of enteric-coated tablets of barium sulphate (diameter 11 mm) remaining in the stomachs of individual humans (n=3), dogs (n=4), mini-pigs (n=3), and stomach-emptying-controlled rabbits (n=5) under fasting conditions, except for rabbits, which were fed after dosing. Five tablets were given to humans, dogs and pigs, and two tablets were given to rabbits (Aoyagi et al., 1992).

Right: fractions of ethyl cellulose-coated granules (diameter 1 mm) remaining in the stomachs of individual humans (n=3), dogs (n=4), mini-pigs (n=3), and stomach emptying-controlled rabbits (n=5) under fasting conditions, except for rabbits, which were fed after dosing. Fifty granules were given to humans and animals (Aoyagi et al., 1992).

Figure 1: differences in gastric emptying between species.

Microbial flora

In species with a low gastric pH the stomach is sterile in the fasting state. The presence of the microflora is governed to a great extent by the acidity of the region. Few bacteria grow at pH 3 or less. However, both food and saliva entering the stomach neutralise gastric acid and allow colonisation by transient flora of predominantly acid-resistant bacteria such as lactobacilli, bacteroides and enterococci. This is the case for humans and rabbit. A higher gastric pH is observed in other species and enables large numbers of bacteria to colonise the stomach. In rodents, the bacterial counts are highest in the anterior part of the stomach. This can be explained by the anatomy of the stomach: rodents display a two-compartment stomach (non glandular and glandular compartment), which permits the bacteria to proliferate faster in the non-acid producing anterior part of the stomach (non-glandular compartment).

The monkey stomach

In the primate family, the anatomy of the stomach varies between the different type of monkeys. This is due to a huge variation in the dietary habits, from insectivores, through omnivores, to types that survive on vegetarian or fruit and nut diets (Jones, 1972). This naturally leads to a range of structural arrangements and relative dimensions within the gastrointestinal tract. For example, some types of monkeys that live on a totally herbivorous diet, such as the leaf eater monkey, have multi compartment stomachs. For the commonly used primates, like the rhesus monkey, the stomach is simple (Dressman and Yamada, 1991).

The pig stomach

The stomach of domestic pigs is much larger than that of humans, in the order of several litres. This is probably partly due to the larger body size, but also may be partly attributed to dietary preferences. Although officially an omnivorous species, domestic pigs are predominantly herbivorous and, as a result, the gastric chamber is somewhat modified. For example, there is a diverticulum or pouch at the top of the stomach which is probably a site for microbial metabolism of ingesta and the percentage of parietal cell-containing mucosa is smaller than in humans (Dressman and Yamada, 1991). Another relevant aspect in pigs lies in their susceptibility to gastric ulcers. Many studies have been conducted in domestic pigs, with the incidence of gastric ulcers reported between 5 and 50% of the general pig population (Pond and Houpt, 1978), with usual incidence of about 20% (Tumbleson, 1986). Pigs restricted to a laboratory setting are often administered cimetidine on a routine basis because of this propensity to ulcers.

The human stomach

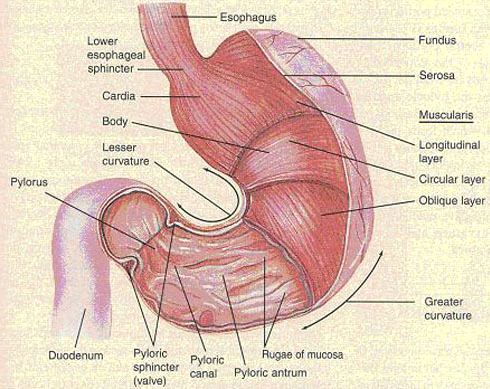

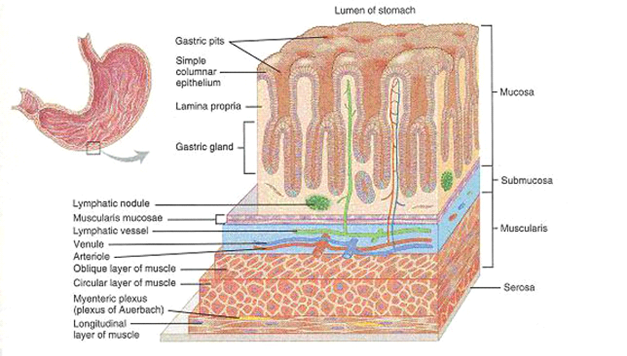

The anatomy of the human stomach is shown in figure 1. The cardia surrounds the superior opening of the stomach. The rounded portion superior to the body and to the left of the cardia is the fundus. Inferior to the fundus is the large central portion of the stomach, called the body. The region of the stomach that connects to the duodenum is the pylorus. It has two parts, the pyloric antrum, which connects to the body of the stomach, and the pyloric canal, which leads into the duodenum. The pylorus communicates with the duodenum of the small intestine via the pyloric sphincter (valve). This valve regulates the passage of chyme from stomach to duodenum and it prevents backflow of chyme from duodenum to stomach (Tortora and Grabowski, 1996). The stomach wall is composed of four layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis and serosal (figure 2).

Figure 2: external and internal anatomy of the stomach of man (Tortora and Grabowski, 1996).

Figure 3: histology of the stomach. a three-dimensional view of layers of the stomach (Tortora and Grabowski, 1996).

Juvenile to adult

During the first days of life, gastric motility is very low. In addition, gastric contractions in neonates are less pronounced than in infants. As a result, the rate of gastric emptying is variable during the neonatal period and is affected by gestational maturity, postnatal age, the type of feeding and clinical disease states (see table). The age at which the gastric emptying time of infants approaches that of adults remains poorly defined, although some authors believe that this transition occurs within the first 6 to 8 months of life (Besunder et al., 1988; Heimann, 1980).

Table 1: Factors affecting the gastric emptying rate in infants (Besunder et al., 1988).

| Increase | Decrease |

|---|---|

| Human milk | prematurity long chain fatty acids gastro-oesophageal reflux congenital heart disease respiratory distress syndrome |